In the 20th century, art moved beyond the canvas and frame and quite literally entered the space of everyday human life. Monumental painting, mosaics, stained glass, reliefs, and the synthesis of the arts became the language of the era — a language used to speak about ideas, memory, identity, faith in the future, or resistance to the system. Building facades, metro stations, houses of culture, and public spaces turned into carriers of meaning that shaped the visual identity of cities and entire generations.

Monumental artists of the 20th century thought on a grand scale: for them, space was not a backdrop but a full-fledged interlocutor. Their works did more than decorate architecture — they transformed its perception, set the rhythm of movement, created atmosphere, and left an emotional imprint for decades to come.

In this selection, we have brought together the Top 5 Ukrainian monumental artists of the 20th century, whose work was defining for its time and continues to influence how we perceive space today. This is a story about art that cannot be ignored — because it becomes part of the city, memory, and our everyday experience.

Mykhailo Boichuk

Mykhailo Boichuk (1882–1937) was a key figure of Ukrainian monumental art of the 20th century and the founder of Boichukism — a unique national style that fused Byzantine heritage, the art of Kyivan Rus, Ukrainian folk painting, and European modernist explorations. He conceived art as a holistic environment meant to be part of everyday life: in churches, public buildings, interiors, streets, and squares. For Boichuk, monumentality meant not only scale but also collectivity — the idea of shared creation and the rejection of individualistic authorship in favor of forming a common cultural language.

Boichuk established a school that educated an entire generation of artists — the Boichukists — who developed his ideas across fresco, mosaic, graphic art, ceramics, and scenography. Although his work did not oppose the ideals of the revolution, his pursuit of national distinctiveness and artistic autonomy rendered the Boichuk school dangerous to the totalitarian system. In 1937, the artist was executed along with his wife and students, and most of his monumental works were destroyed. Yet Boichuk’s ideas outlived the physical annihilation of his legacy: they became a foundation of Ukrainian monumentalism in the 20th century and an essential part of the cultural memory of the Executed Renaissance.

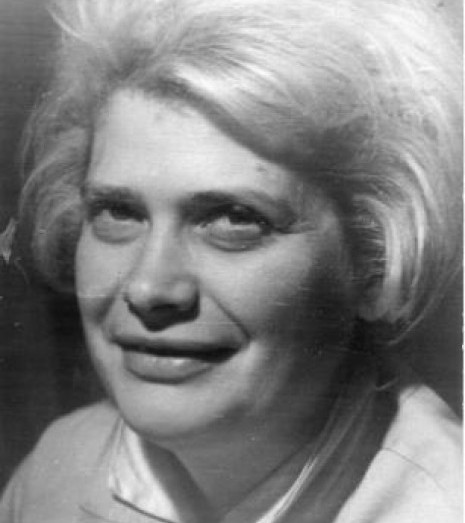

Alla Horska

Alla Oleksandrivna Horska (September 18, 1929 — November 28, 1970) entered the history of Ukrainian art as one of the most powerful figures of 20th-century monumentalism and a symbol of artistic resistance. Working with mosaics, stained glass, and monumental painting, she conceived space as a public tribune — a place where art speaks about dignity, memory, and national identity. Her monumental works combined traditions of Ukrainian folk art, the Kyiv academic school, Boychukism, and modernist explorations, forming a new, distinctly Ukrainian visual language in defiance of the ideological pressure of the Soviet system.

Horska’s practice went far beyond aesthetics — her art was an act of civic stance. The stained-glass work “Shevchenko. Mother” (1964), created in collaboration for the Red Building of Kyiv University and destroyed by the authorities as “ideologically hostile,” became one of the key gestures of cultural resistance of the 1960s. Working on monumental panels in Kyiv, Donetsk, and Krasnodon together with a circle of like-minded artists, Horska introduced ideas of freedom, human responsibility, and historical truth into public space. Her tragic death at the age of 41 only underscored the scale of her legacy: Alla Horska left behind not only an artistic heritage, but also an ethical dimension of monumental art — as an art form that shapes consciousness and refuses to remain silent.

Tetiana Yablonska

Tetiana Nylivna Yablonska (1917–2005) is best known as a painter, yet her contribution to 20th-century monumental art is no less significant. As an artist who thought in terms of spatial scale and the interaction between art and architecture, she worked toward shaping an integral artistic environment in which image, rhythm, and color were subordinated to the logic of space. In the 1960s, Yablonska actively engaged in the development of monumental painting, combining a strong academic foundation with the search for new imagery, an engagement with folk art, and a generalized, symbolic visual language.

A special role in her monumental practice was played by her pedagogical and curatorial work: from 1966 to 1973, Yablonska headed the monumental painting studio at the Kyiv State Art Institute, educating a generation of artists for whom the synthesis of art and space became a core principle. For her, monumentality was not merely a form but a way of thinking — the ability to speak about the human condition, labor, life, and time through broad artistic generalization. Even while working within the framework of the official system, Yablonska maintained artistic freedom and a strong inner ethical stance, which secured her place as one of the central figures of Ukrainian art of the 20th century and a key contributor to the history of national monumentalism.

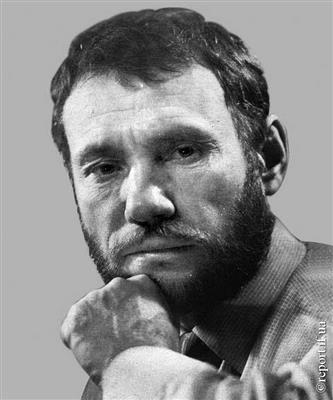

Ivan-Valentyn Zadorozhnyi

Ivan-Valentyn Feodosiiovych Zadorozhnyi (1921–1988) was one of the most distinctive figures of Ukrainian monumental art in the second half of the 20th century. Born in Rzhyshchiv into a peasant family, he lived through a dramatic life path: a childhood shattered by the Holodomor, early years marked by loneliness, frontline experience and wounds during World War II, and later a return to Kyiv to study at the Kyiv State Art Institute (1945–1951) under Kostiantyn Yeleva, Anatol Petrytskyi, and Serhii Hryhoriev. War and personal loss shaped his profound historical consciousness and heightened sense of human dignity, which would become defining qualities of his art.

Zadorozhnyi fully established himself as a monumental artist from 1966, when he joined the monumental art section. His works — stained glass, carving, and integrated interior ensembles — are distinguished by a synthesis of epic scale, symbolism, and national-historical meaning. Among his key monumental projects are the stained-glass composition Taras Shevchenko and the People (co-authored), Our Song Is Our Glory in Kremenchuk, People, Protect the Earth! in Bila Tserkva, the stained-glass windows of the upper station of the Kyiv Funicular, and the Bratyna hall in the Lybid Hotel. In parallel, he created painted “parsuny” of historical figures—from Yaroslav the Wise to Yurii Kondratiuk — constructing a continuous visual narrative of Ukrainian history. The posthumous awarding of the Shevchenko National Prize (1995) recognized his role as an artist who conceived space through history and understood monumentality as a form of cultural memory.

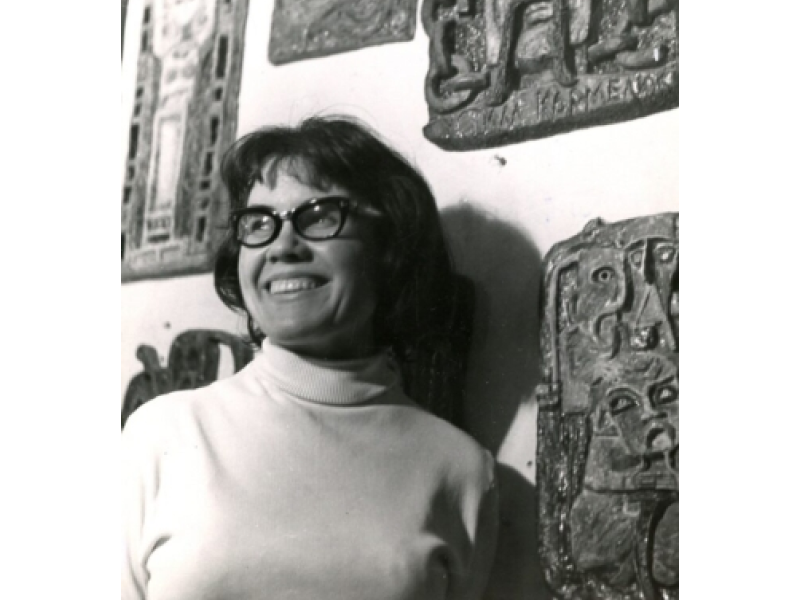

Halyna Sevruk

Halyna Sylvestrivna Sevruk (1929–2022) was one of the key figures of Ukrainian monumental art in the second half of the 20th century — a ceramic artist whose work united the archaic power of material with profound historical and national meaning. Working in ceramics, mosaic, and graphic art, she created monumental images rooted in Ukrainian mythology, literature, and history. Sevruk belonged to the generation of the Sixtiers and was an active member of the Creative Youth Club Suchasnyk, where art was shaped as a space of freedom, memory, and resistance. Her participation in the stained-glass window "Shevchenko. Mother" (1964), destroyed by the authorities, became one of the emblematic acts of cultural resistance of the era.

Sevruk conceived space through image and material: her ceramic panels and sculptural reliefs carried epic generalization while preserving a deeply human intonation. Among her landmark works are Yaroslavna, Lada, and the large-scale panel City on Seven Hills (1985–1987), dedicated to the history of Kyiv and marking the culmination of her monumental explorations. Despite repression—her expulsion from the Union of Artists in 1968 for her civic stance—Sevruk maintained artistic independence and consistency. Her monumental art became a form of enduring memory: a language that, through clay and stone, speaks of cultural continuity, dignity, and the right to one’s own history.

Monumental art of the 20th century in Ukraine became not only an artistic practice but also a way of thinking— a means of speaking to society through space, image, and memory. The work of Alla Horska, Tetiana Yablonska, Ivan-Valentyn Zadorozhnyi, Mykhailo Boichuk, and Halyna Sevruk demonstrates how art can shape identity, resist oppression, preserve history, and remain alive within everyday environments.

Their works still remind us that monumental art cannot be merely “viewed” — it is something we coexist with. It becomes part of the city, lived experience, and collective memory, continuing to influence our perception of space and culture decades later.

На заставці: розпис Харківського Червонозаводського театру - Свято врожаю. 1935 рік. Михайло Бойчук

(1)_latest.webp)

_latest.webp)