In the second half of the 20th century, a new generation emerged in Ukrainian art — one that broke the canons of socialist realism and asserted the artist’s right to freedom. The Sixtiers were artists, poets, filmmakers, and thinkers for whom creativity became a form of resistance to the totalitarian system. They restored to art the national symbols, philosophical depth, human dignity, and truth that the regime had tried to erase for decades.

This article tells the story of eight Ukrainian Sixtier artists whose work became both an artistic and civic manifesto. Their paintings, graphics, and sculptures are not merely images — they are symbols of freedom that continue to inspire today.

Alla Horska

Alla Horska was one of the most prominent figures of the Ukrainian Sixtier movement — an artist, monumental painter, and human rights activist who turned her life into an act of civic resistance. Her art combined folk traditions, the power of monumental form, and a sincere protest against totalitarianism. Together with her husband, Viktor Zaretskyi, she created mosaics, paintings, and stained-glass works that radiated the spirit of freedom even in times of strict Soviet censorship.

As a co-founder of the Club of Creative Youth Suchasnyk, Alla Horska took part in uncovering mass graves of repression victims in Bykivnia, supported persecuted artists, and initiated public actions in honor of Taras Shevchenko. Her fearlessness and devotion to truth made her a symbol of artistic resistance. After her brutal murder in 1970 — likely orchestrated by Soviet security services — Horska remained in memory as a personification of indomitable spirit and the struggle for human and national dignity.

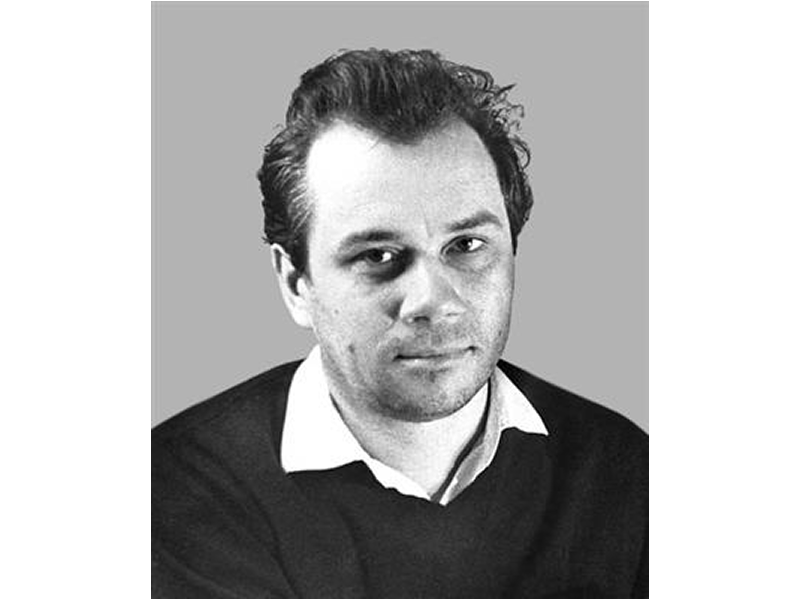

Viktor Zaretskyi

Viktor Zaretskyi (1925–1990) was a Ukrainian modernist artist often called the “Ukrainian Klimt.” His style combined the traditions of Boichukism, European Art Nouveau, and folk symbolism. After the war and his studies at the Kyiv Art Institute, he developed his own artistic language, where the emotional power of color and line conveyed deep spiritual meaning. In collaboration with Alla Horska, Zaretskyi created monumental mosaics that became symbols of freedom and national dignity.

As a member of the Sixtier movement and the Club of Creative Youth Suchasnyk, Zaretskyi supported dissidents and spoke out against repression. After Horska’s death, he devoted himself to painting, developing a distinctive style of “Ukrainian Neo-Art Nouveau.” His works, filled with symbolism and drama, became a powerful expression of the struggle for spiritual freedom. Posthumously, the artist was awarded the Shevchenko National Prize in 1994.

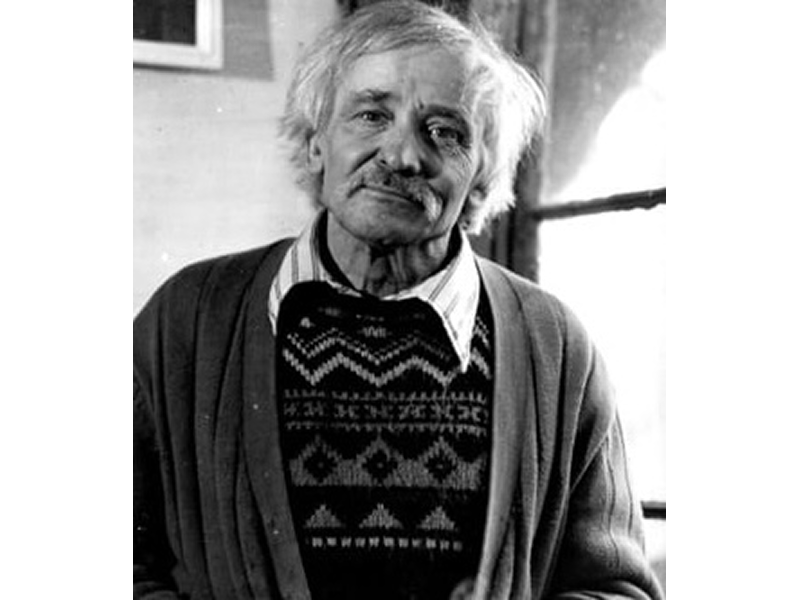

Opanas Zalyvaha

Opanas Zalyvaha (1925–2007) was a Ukrainian painter and one of the leading figures of the Sixtiers movement, whose art became a symbol of spiritual resistance to the Soviet regime. Born in the Kharkiv region, he studied at the Repin Institute in Leningrad before settling in Ivano-Frankivsk. His paintings, filled with symbolism and love for Ukraine, were often condemned by the authorities for their open yearning for freedom.

Zalyvaha was an active human rights advocate, a member of the Club of Creative Youth, a co-author of the destroyed stained glass piece “Shevchenko. The Mother,” and one of the signatories of the “Letter of 139.” For his convictions, he spent five years in Mordovia labor camps but never renounced his ideals. After his release, he continued to create and, in independent Ukraine, became a renowned artist and teacher. His life and art remain enduring symbols of the resilience and freedom of the Ukrainian spirit.

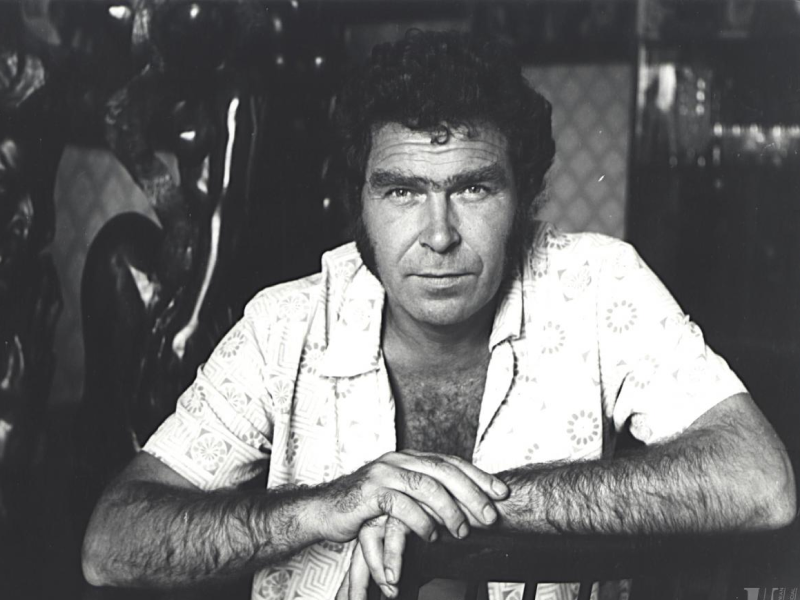

Borys Plaksii

Borys Plaksii (1937–2012) was a Ukrainian painter, monumental artist, sculptor, and graphic artist whose work became a symbol of artistic dignity and civic courage. One of the brightest representatives of the Sixtiers movement, he gained recognition in the 1960s as a talented monumental artist and creator of striking designs in Kyiv’s public spaces. His career was shattered after he signed a protest letter against the return of Stalinism — as a result of his defiance, Plaksii was banned from exhibiting, and many of his works were destroyed.

Despite persecution, he never renounced his beliefs and continued to create. More than a thousand of his works form a chronicle of the Ukrainian spirit, filled with depth and humanity. Plaksii portrayed many artists and dissidents, and for his contribution to the exhibition “Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence” at the Ivan Kavaleridze Museum-Workshop, he was awarded the Shevchenko National Prize. His life and art stand as a testament to resilience and fidelity to freedom.

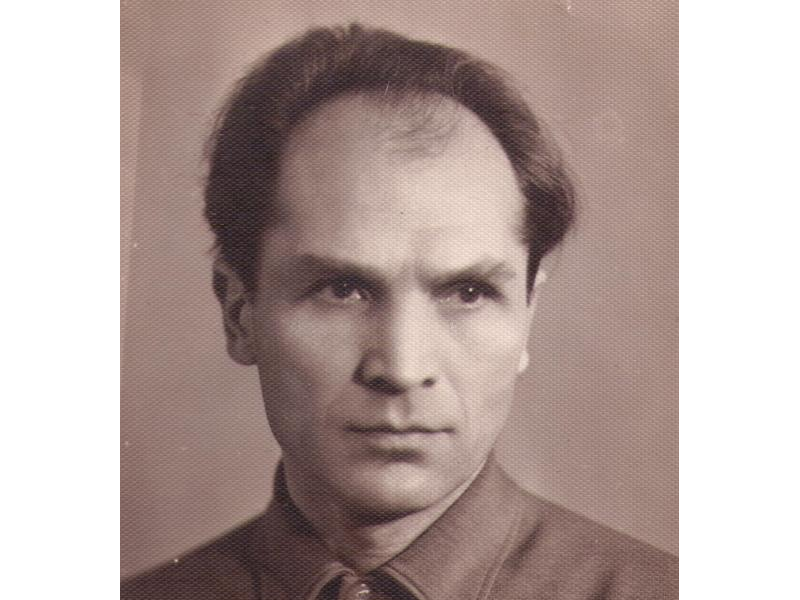

Veniamin Kushnir

Veniamin Kushnir (1926–1992) was a Ukrainian painter, educator, and representative of the Sixtiers generation. He was born on January 7, 1926, in the village of Rudka in Podillia. From an early age, he showed a talent for drawing, and after serving in the army, he fully devoted himself to art. He studied at the Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts under Roman Selskyi, Yosyp Bokshai, and Ivan Hutorov. He worked in Dnipropetrovsk, and from 1956 in Kyiv, where he created his first notable works — “Lumberjacks,” “Raftmen,” “Red Poppies,” and “Trembita” — exploring themes of spiritual strength and national revival.

In the 1960s, Kushnir was an active member of the Club of Creative Youth “Suchasnyk” and maintained close ties with Vasyl Symonenko, Alla Horska, and Yevhen Sverstiuk. His art stood out for its symbolism and deep national meaning, which led to persecution by the authorities. Among his most famous works are “Kobza,” “Scherzo,” “Prometheus,” “Mothers,” and “Dovbush,” as well as a series inspired by Shevchenko. In his later years, he created philosophical paintings such as “Earth,” “Mother and Son,” and “Self-Portrait with a Candle.” Kushnir’s legacy stands as a powerful testament to spiritual resistance and the affirmation of Ukrainian national consciousness.

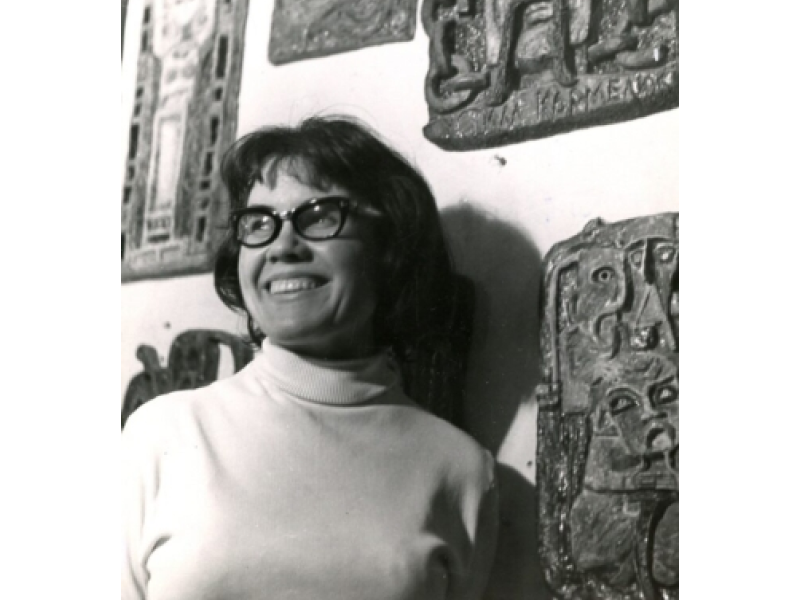

Halyna Sevruk

Halyna Sevruk (1929–2021) was a Ukrainian artist, sculptor, ceramist, and graphic artist — a prominent representative of the Sixtiers, Honored Artist of Ukraine, and laureate of the Vasyl Stus and Andrey Sheptytsky Prizes. She was born in Samarkand and, from 1930, lived in Ukraine. A graduate of the Art School at the Kyiv Art Institute, she was an active member of the Club of Creative Youth “Suchasnyk” and maintained close ties with leading figures of the Ukrainian cultural movement. Her stained-glass work “Shevchenko. Mother” (1964) was destroyed by the authorities as “ideologically hostile.”

After signing the “Letter of Protest of the 139,” Sevruk was expelled from the Union of Artists and banned from exhibiting for many years. Despite this, she created dozens of monumental and smaller-scale works — including the mosaics “Forest Song,” “Lileya,” the panel “The City on Seven Hills,” and the series “The Cossack Era.” Her art, imbued with historical memory and national spirit, remains a vital page in the history of Ukrainian culture.

Liudmyla Semykina

Liudmyla Semykina (1924–2021) was a Ukrainian artist, master of decorative art, costume designer, dissident, and active participant in the national movement of the 1960s–1970s. She was born in Odesa and studied at the Odesa Art School and the Kyiv Art Institute. A member of the Club of Creative Youth, together with Alla Horska and other artists, she raised issues concerning the preservation of Ukrainian culture and language. Her stained glass work "Shevchenko. The Mother" (1964) was destroyed by the authorities as “ideologically hostile.” For her civic stance, Semykina was twice expelled from the Union of Artists and deprived of the opportunity to work in her profession.

Despite persecution, she found herself in creating clothing inspired by Ukrainian traditions and later became a costume designer for theater and film — she designed the costumes for the film "Zakhar Berkut" (1971). Her art series "Scythian Steppe," "The Princely Era," and "The High Castle" earned her the Shevchenko National Prize in 1997. Semykina remained a symbol of creative freedom and inner dignity, embodying the Ukrainian spirit in art even in times of prohibition. She passed away in 2021 and was buried at Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

Stefania Shabatura

Stefania Shabatura (1938–2014) was a Ukrainian tapestry artist, dissident, and member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. She was born in Ternopil region and graduated from the Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts. She worked in textile art, participated in exhibitions, was a member of the “Prolisok” Club of Creative Youth, supported the resistance movement, and distributed samizdat publications.

In 1972, she was sentenced to five years in labor camps and three years in exile for “anti-Soviet activity.” After returning to Lviv, she became active in the “Memorial” society and the People’s Movement of Ukraine (Rukh), and participated in the revival of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. As a deputy of the Lviv City Council in 1990, she and her colleagues raised the blue-and-yellow flag over the City Hall. She died in 2014 and was buried at Lychakiv Cemetery.

Alla Horska, Opanas Zalyvaha, Borys Plaksiy, Viktor Zaretskyi, Veniamin Kushnir, Halyna Sevruk, Liudmyla Semykina, and Stefania Shabatura, through their art and civic stance, challenged the system that sought to suppress the uniqueness of Ukrainian art.

Their legacy is not only an aesthetic phenomenon but also a moral compass. They proved that art can be a form of resistance, a voice of truth, and a symbol of dignity. Thanks to their courage and talent, Ukrainian culture preserved its living connection to its roots and opened a new page in its history.

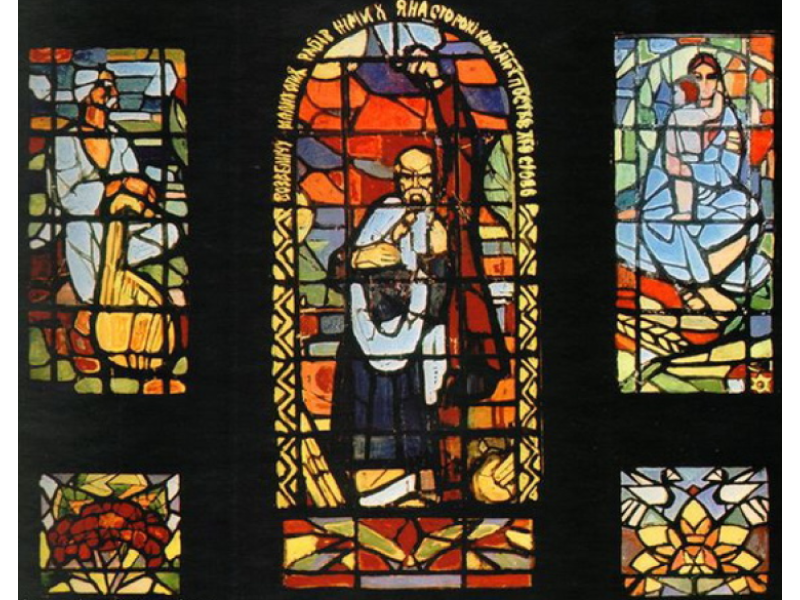

On the cover: sketch for the stained glass “Shevchenko. The Mother” for the Kyiv Art Institute.

(1)_latest.webp)

_latest.webp)